Overview

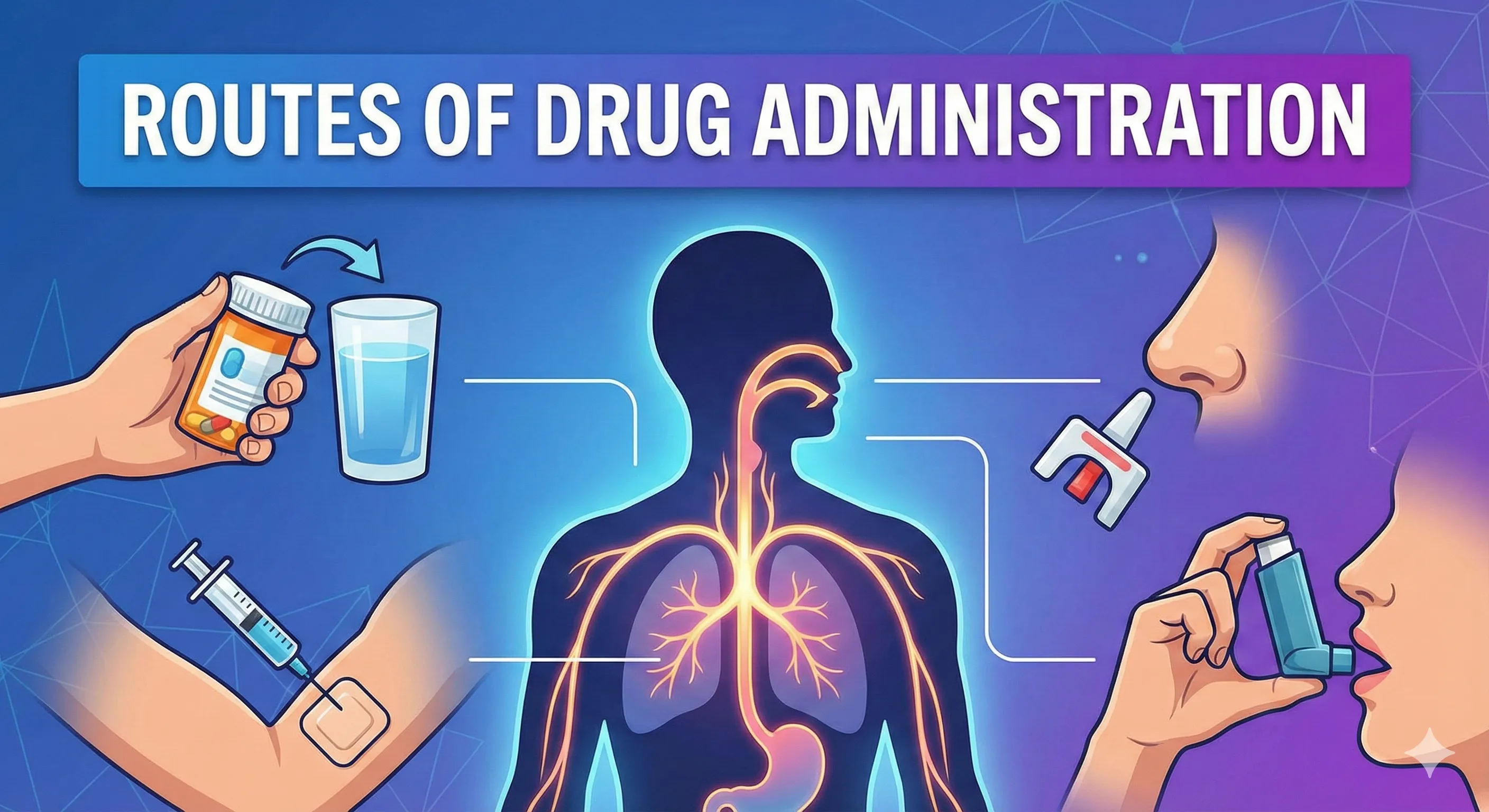

A drug’s route of administration is the pathway by which the active substance is delivered to achieve local or systemic therapeutic effect, and the choice of route shapes onset, intensity, duration, and safety by determining absorption, first-pass metabolism, and bioavailability. The same active molecule can yield very different clinical results depending on whether it is given orally, sublingually, intravenously, intramuscularly, subcutaneously, via inhalation, transdermally, or through specialized routes such as intrathecal or intranasal delivery.

Why routes matter

- Route selection is driven by drug physicochemical properties, desired site of action (local vs systemic), required speed of onset, first-pass metabolism, patient condition, and practical considerations of dose accuracy, sterility, and adherence.

- Aligning route with pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics improves therapeutic benefit and reduces risk, which is why foundational pharmacology texts discuss “drug absorption and routes of administration” together.

Core classification

- Systemic routes: enteral (oral, sublingual/buccal, rectal) and parenteral (IV, IM, SC, intra-arterial, intradermal, intrathecal, intraosseous), plus inhalational, transdermal, and intranasal; each can deliver drugs into the systemic circulation with differing extents of first-pass and barriers.

- Local routes: topical to skin and mucosa (ocular, otic, nasal, oropharyngeal, rectal/vaginal local therapy), intra-articular, intravitreal, and device-based elution (e.g., drug-eluting stents) primarily for site-specific effects.

Factors guiding route choice

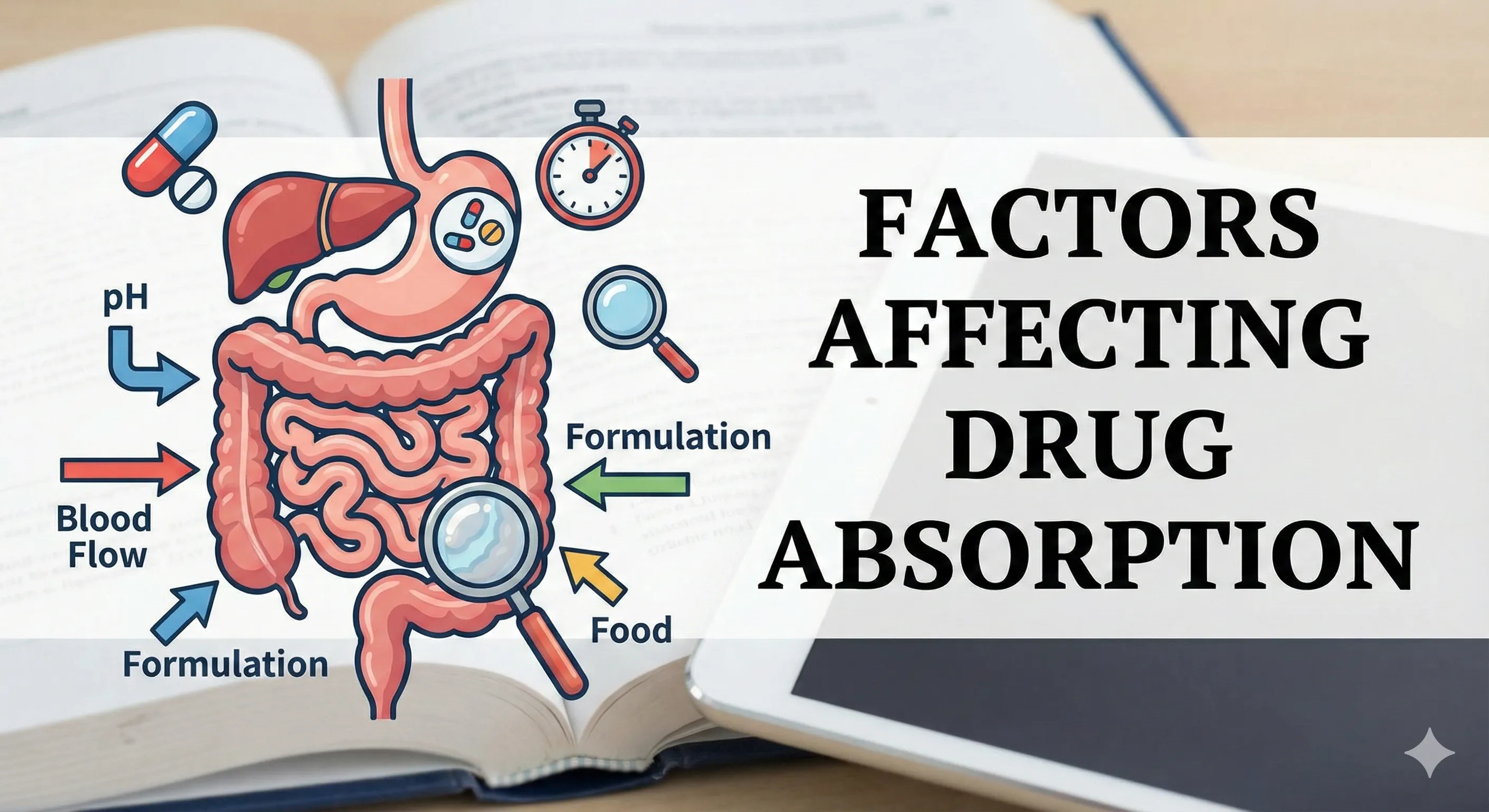

- Drug-related: solubility, stability in GI fluids, permeability across epithelia, irritancy, dose size, need to bypass first-pass, and suitability for depot or controlled-release formulations.

- Patient-related: consciousness, swallowing ability, vomiting, comorbidities (coagulopathy for IM), vascular access, preferences, cultural considerations, and care setting (e.g., home palliative care using rectal route).

Key pharmacokinetic principles

- Bioavailability and first-pass: IV administration delivers immediate systemic exposure with near-total bioavailability, whereas oral drugs face variable dissolution, absorption, and presystemic metabolism; sublingual/buccal and inhaled routes bypass first-pass, while rectal absorption partially bypasses it.

- Barriers and surfaces: the small intestine offers large absorptive area for oral drugs; pulmonary alveoli provide a surface area of roughly tens of square meters enabling rapid systemic uptake of gases and aerosols when particle size is optimized (11–10 μm10 μm).

Enteral routes

Oral (per os)

- Description and kinetics: Most common and convenient; absorption mainly in the small intestine with variability introduced by formulation, gastric emptying, intestinal motility, food effects, solubility, and first-pass metabolism.

- Advantages: Noninvasive, widely acceptable, suitable for sustained-release forms when steady exposure is desired; best for chronic therapy and self-administration.

- Limitations: Variable absorption, potential degradation in GI tract, limited permeability for large or highly polar molecules, first-pass inactivation, GI irritation, and unsuitability in vomiting or altered consciousness.

Sublingual and buccal

- Description and kinetics: Drug placed under the tongue or in the buccal pouch gains rapid access to systemic veins draining to the superior vena cava, thus bypassing hepatic first-pass metabolism; sublingual mucosa is more permeable than buccal.

- Advantages: Rapid onset, avoidance of first-pass, utility in high first-pass drugs (e.g., nitroglycerin), option to remove the dosage form if adverse effects emerge, and feasibility in dysphagia.

- Limitations: Dose size constraints, taste/palatability issues, salivation variability, and the need to refrain from swallowing or chewing.

Rectal

- Description and kinetics: Highly vascular mucosa supports effective absorption, with about half of the absorbed drug avoiding the portal vein, thereby partially bypassing hepatic first-pass; useful when oral route is not feasible.

- Advantages: Suitable for patients with dysphagia, vomiting, severe nausea, or at end of life; stable against gastric acid and pancreatic enzymes; can be used in emergencies (e.g., pediatric seizures).

- Limitations: Variable absorption of hydrophilic/peptide drugs, local irritation/proctitis, limited patient acceptability, and procedural constraints after rectal or bowel surgery.

Parenteral routes

Intravenous (IV)

- Description and kinetics: Direct entry into systemic circulation yields rapid onset, predictable exposure, and circumvents first-pass; peripheral access is usually via metacarpal, basilic, or cephalic veins, while central venous lines support special infusions.

- Advantages: Immediate effect, titratability, reliable bioavailability, utility in emergencies, comatose states, and for poorly absorbed or GI-unstable drugs.

- Limitations: Pain, infection risk, extravasation (and potential tissue necrosis with vesicants), need for sterile technique, and the possibility of abrupt systemic toxicity with rapid exposure.

Intramuscular (IM)

- Description and kinetics: Drug deposited into muscle (deltoid, vastus lateralis, ventrogluteal) is absorbed through capillary beds; depot formulations can sustain release over weeks.

- Advantages: Useful when oral absorption is erratic or extensive first-pass reduces efficacy; depot preparations enable long-acting therapy (e.g., haloperidol decanoate), and vaccines are commonly administered IM.

- Limitations: Injection pain, volume limits dictated by muscle mass, local degradation of peptides, and complications including hematoma, abscess, nerve injury (e.g., sciatic with dorsogluteal injections), and inadvertent intravascular injection.

Subcutaneous (SC)

- Description and kinetics: Injection into the hypodermis provides slower, sustained absorption due to relative avascularity; commonly used for insulin, heparin, and biologics.

- Advantages: Ease of self-administration, improved bioavailability over oral for some drugs, and modifiable absorption (e.g., hyaluronidase).

- Limitations: Variable absorption rate, local pain/irritation, need to rotate sites to prevent lipohypertrophy or lipoatrophy that alter drug uptake.

Intra-arterial, intradermal, intrathecal, epidural, intraosseous

- Intra-arterial: Rarely used but valuable for selective chemotherapy and angiographic contrast delivery to limit systemic exposure while maximizing regional effect.

- Intradermal: Small-volume delivery into dermis for diagnostic testing or specific immunization strategies when antigen-presenting cells are targeted.

- Intrathecal/epidural: Direct CNS delivery bypasses blood–brain barrier for analgesia, antispasticity, or chemotherapy; requires stringent asepsis and specialized training.

- Intraosseous: Emergency alternative to vascular access (e.g., in neonates or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest) enabling rapid systemic delivery via marrow sinusoids.

Inhalational and pulmonary routes

- Description and kinetics: Aerosolized or gaseous drugs traverse the respiratory epithelium into pulmonary circulation and then systemic circulation via pulmonary veins, avoiding first-pass; efficacy depends on particle size (11–10 μm10 μm), device, and respiratory pattern.

- Advantages: Large absorptive surface, rapid onset, lower systemic doses needed for equivalent effect, and direct local delivery for airway diseases (e.g., inhaled steroids, bronchodilators).

- Limitations: Mucus clearance and airway filters limit deposition, with only 1010–40%40% of a conventional device dose reaching the lungs; technique-dependent and device-specific training required.

Transdermal and topical routes

- Transdermal: Drug permeates stratum corneum for systemic effect; technologies include patches, gels/ointments, lipid vesicles, microneedles, and iontophoresis, supporting controlled delivery and avoidance of first-pass.

- Topical: Localized therapy to skin or mucosa for dermatologic, ophthalmic, otologic, or nasal conditions minimizes systemic exposure; formulation and site determine penetration and effect.

Intranasal route

- Description and kinetics: Single-layered, well-vascularized respiratory epithelium enables rapid systemic absorption while bypassing first-pass; bioavailability depends on secretion rate, ciliary movement, local enzymes, vascularity, and disease state.

- Advantages: Quick onset within minutes, convenient noninvasive delivery (e.g., desmopressin, calcitonin, some emergency agents), and utility when GI routes are compromised.

- Limitations: Limited dose capacity, variable absorption in rhinitis or mucosal disease, potential for local irritation, and not suitable for all drugs.

Vaginal route

- Description and kinetics: Venous drainage patterns allow partial bypass of hepatoportal circulation; supports both local (e.g., antifungals) and systemic delivery (e.g., hormones) via tablets, gels, creams, pessaries, or rings.

- Advantages: Avoids first-pass, sustained low-dose delivery for stable levels, and an alternative route for reproductive or pelvic indications.

- Limitations: Formulation acceptability, local irritation, and patient-specific preferences or cultural factors that may affect adherence.

Ocular, intravitreal, and device-based routes

- Ocular topical delivery provides local effects with lacrimal drainage and corneal barriers limiting systemic exposure; specialized intravitreal injection can deliver high intraocular drug concentrations in posterior segment disease.

- Device-based elution (e.g., drug-eluting stents) provides local controlled release at vascular or other interfaces where sustained peridevice concentrations are desired.

Comparative tables

Table 1. Overview of major routes, key advantages and limitations, and representative uses.

| Route | Key advantages | Key limitations | Typical uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Convenient, noninvasive; suitable for sustained release; broad patient acceptance | Variable absorption; first-pass metabolism; unsuited in vomiting or reduced consciousness | Chronic systemic therapy; self-administered medications |

| Sublingual/buccal | Rapid onset; bypasses first-pass; removable if adverse effect occurs | Dose size/taste constraints; requires not swallowing | Nitroglycerin for angina; selected analgesics |

| Rectal | Partial first-pass bypass; useful in dysphagia/vomiting; pediatric emergencies | Variable absorption; local irritation; acceptability issues | Anticonvulsants in children; palliative care medications |

| IV | Immediate effect; predictable exposure; for GI-unstable or poorly absorbed drugs | Pain/infection risk; extravasation; requires skill/asepsis | Emergencies; anesthetics; antibiotics; chemotherapy |

| IM | Depot feasibility; vaccines; avoids first-pass | Injection pain; nerve/vascular injury risk; volume limits | Long-acting antipsychotics; vaccines; hormones |

| SC | Ease of self-use; sustained absorption; better bioavailability than oral for some drugs | Variable absorption; local reactions; rotate sites | Insulin; heparin; monoclonal antibodies |

| Inhalational | Rapid pulmonary/systemic uptake; small doses sufficient; local airway therapy | Technique/device dependent; 10–40% lung deposition | Bronchodilators; inhaled steroids; anesthetic gases |

| Transdermal | Controlled systemic delivery; avoids first-pass; improved adherence | Skin barrier limits candidates; irritation; patch limits | Nicotine, fentanyl, hormones, clonidine patches |

| Intranasal | Fast systemic absorption; first-pass bypass; noninvasive | Limited dose; mucosal disease alters uptake | Desmopressin; calcitonin; selected emergency drugs |

Table 2. Parenteral injection routes: practical notes and complications.

| Route | Sites and technique highlights | Common complications |

|---|---|---|

| IV | Peripheral veins (metacarpal, basilic, cephalic); remove tourniquet before injection; ultrasound for central/PICC placement | Infiltration vs. extravasation; infection; thrombosis; rapid systemic toxicity with bolus |

| IM | Prefer ventrogluteal, deltoid, vastus lateralis; perpendicular angle; aspirate for dorsogluteal proximity to vessels | Hematoma/abscess; sciatic/radial/axillary injury; inadvertent intravascular injection |

| SC | Rotate sites (arm, abdomen away from navel, thigh, upper back); adjust angle with pen vs syringe | Local pain/irritation; lipohypertrophy/lipoatrophy; variable absorption |

| Intraosseous | Emergency access in neonates and cardiac arrest; tibial or other sites per protocol | Local injury/infection; extravasation into compartments if misplacement |

| Intrathecal/epidural | Specialized sterile technique; pumps/catheters for chronic therapy | Infection; neurological injury; dosing errors with high-risk medications |

Table 3. First-pass metabolism and onset by major routes.

| Route | First-pass exposure | Typical onset |

|---|---|---|

| Oral | Yes (hepatic and gut wall) | Variable; minutes to hours depending on formulation |

| Sublingual/buccal | No (drains to SVC) | Rapid; minutes |

| Rectal | Partial (about half bypasses portal vein) | Variable; often faster than oral for some drugs |

| IV | No (direct systemic) | Immediate |

| IM | No (systemic via muscle capillaries) | Minutes to tens of minutes; depot extends days–weeks |

| SC | No (systemic via subcutaneous tissues) | Slower than IM; sustained |

| Inhalational | No (pulmonary to systemic) | Rapid; minutes; device/particle-size dependent |

| Transdermal | No (systemic via skin) | Slow; controlled; hours to days depending on system |

| Intranasal | No (systemic via nasal mucosa) | Rapid; minutes |

Technique and safety highlights

- The “five rights” (right patient, drug, dose, site, timing) are essential to safe administration across routes; sterile technique and appropriate equipment selection reduce complications.

- For IM injections, perpendicular needle entry with attention to safe sites (prefer ventrogluteal over dorsogluteal) reduces nerve/vascular injury; for SC insulin, site rotation mitigates lipohypertrophy and erratic absorption.

Route-specific pearls for MBBS exams

- Nitroglycerin is placed sublingually to bypass extensive first-pass metabolism (greater than 90%90% hepatic clearance on a single pass), enabling rapid relief of angina.

- Rectal administration partially bypasses the liver (superior hemorrhoidal vein drains to portal system; middle and inferior to systemic), explaining intermediate first-pass effects.

- Inhaled drugs often require smaller total doses to achieve airway effects and can reduce systemic adverse effects, though deposition is only 1010–40%40% without optimized technique and devices.

Special populations and settings

- Pediatrics: Rectal route in seizures when IV access is delayed; intraosseous access for rapid systemic therapy when venous cannulation fails; SC and IM volume limits adjusted to size.

- Palliative care and end-of-life: Rectal, sublingual, and transdermal routes maintain comfort and continuity when oral intake is compromised.

Decision-making framework

- Define therapeutic goal and required onset (immediate vs controlled), then match route to properties: IV for emergencies; sublingual for rapid relief in high first-pass drugs; inhalation for local airway disease; transdermal for steady systemic exposure; oral for chronic convenience; IM depot for adherence challenges; specialized routes for CNS or regional targeting.

- Check contraindications: avoid oral in vomiting/altered consciousness, IM in severe coagulopathy/myopathy/infected sites, rectal after colorectal surgery or in active proctitis, and intranasal in severe mucosal disease or obstruction.

Device- and procedure-enabled delivery

- Pulmonary devices: MDIs, DPIs, nebulizers require technique training (shake, inhale through mouth, slow deep inspiration, hold breath 55–1010 s, spacer use) to improve lung deposition and outcomes.

- Regional vascular/CNS delivery and drug-eluting implants or stents achieve high local concentrations with lower systemic exposure but require procedural expertise and attention to sterile technique.

Complications overview

- Parenteral: pain, bleeding, hematoma, infection, extravasation (especially with vesicants), nerve injuries at IM sites, thrombosis with central lines, and systemic toxicity with rapid IV exposure.

- Mucosal/topical: local irritation, steroid-associated nasal septal issues, oral candidiasis with inhaled steroids without rinse/spacer, dermatitis with transdermal systems.

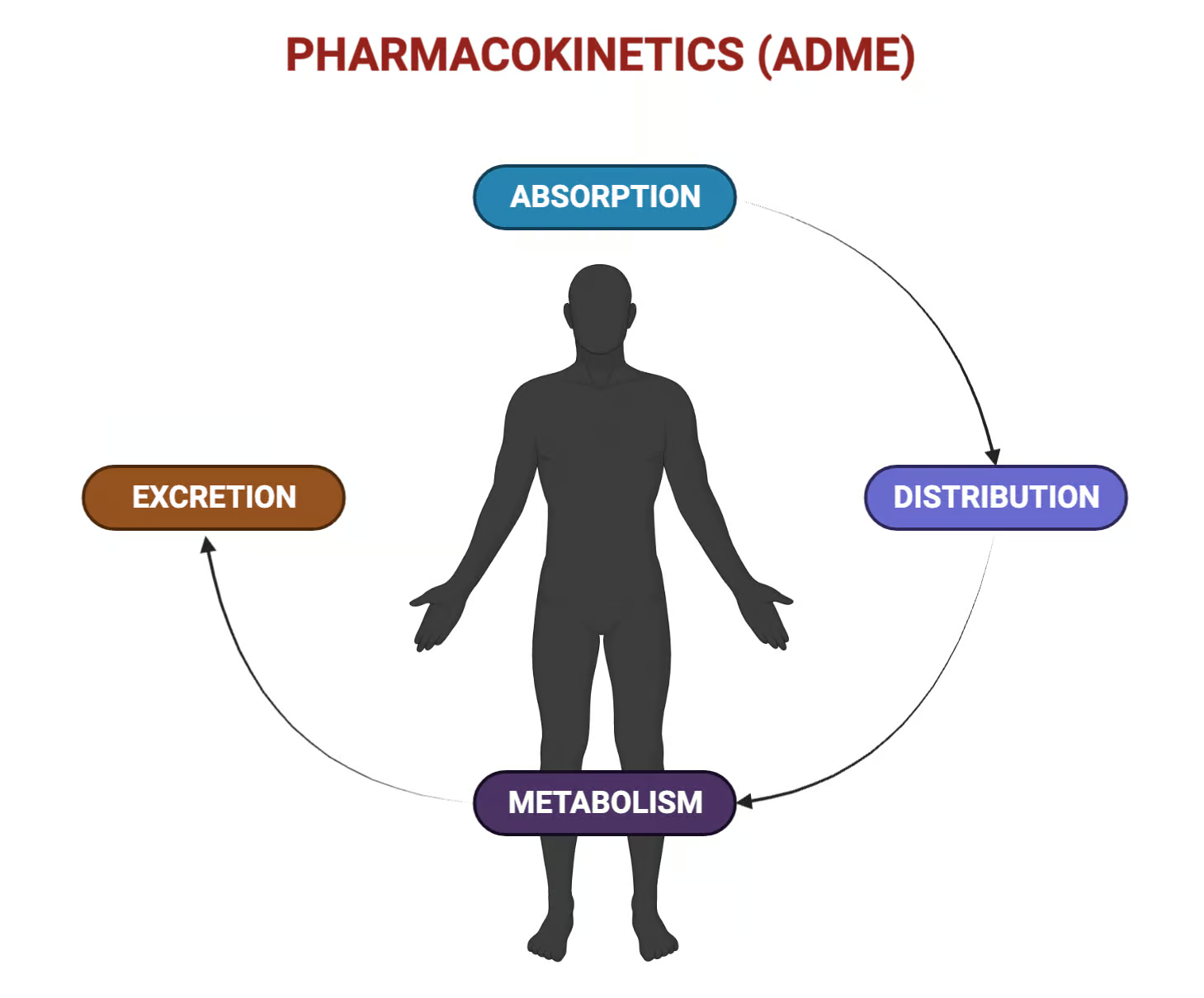

Integrating with pharmacokinetics

- Matching route to avoid first-pass when needed, harness depot kinetics (IM oils, SC implants), exploit large absorptive surfaces (intestine, lung), or bypass barriers (BBB via intrathecal) makes route choice a central lever in designing rational regimens taught in standard pharmacology curricula.

Extended reading and canonical context

- Standard texts integrate routes with absorption and distribution because route alters the concentration–time profile, which determines efficacy and safety; MBBS education emphasizes these links early in training.

- Summative tables of route advantages/disadvantages in clinically oriented resources derive from canonical chapters in Goodman & Gilman and Katzung, reflecting consistent principles across references.

Examination-oriented summary points

- Oral is default for chronic therapy but limited by first-pass and GI variability; sublingual/rectal bypass first-pass partially or completely; IV is immediate and titratable; IM/SC allow depot or self-administration; inhaled and transdermal optimize local or controlled systemic delivery; intranasal is fast and noninvasive; specialized routes target CNS or regions.

- Technique, contraindications, and complication prevention are as critical as pharmacology to clinical success with any route.

References

- Tripathi KD. Essentials of Medical Pharmacology. 6th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2008.

- Ritter JM, Flower R, Henderson G, Loke YK, MacEwan D, Robinson E, Fullerton J. Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology. 10th ed. London: Elsevier; 2024.

- Kim J, De Jesus O. Medication Routes of Administration. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023–2025.

- Deranged Physiology. Routes of administration. Cites Goodman & Gilman (11th ed) and Katzung (11th ed) for tabulated advantages/limitations. 2023.

- Huang X, Wang X, Zhang J, et al. The optimal choice of medication administration route regarding intravenous, intramuscular, and subcutaneous injection: a comparative review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:1869–75.